Me, Angela Davis, and A Hopeful Feminism

How My Love for Angela Davis Helped Me Cultivate a Politics of Hope

I’m a really bad cynic. I remember sitting in graduate seminars and feeling unsure of myself because I didn’t come away from the readings with a negative take of the readings. I did not immediately see what was problematic. Rather, I had a much more generous reading of the text. I know now that I lean towards possibility but then, surrounded by so many people who was what was lacking, I thought maybe I missed something. Lately, I have been feeling this way again and find myself wondering I am naïve to be feeling hopeful in the midst of an imploding empire? And how the hell did I, a girl who had a life that no one would categorize as easy, build a feminist consciousness around optimism, possibility, and hope?

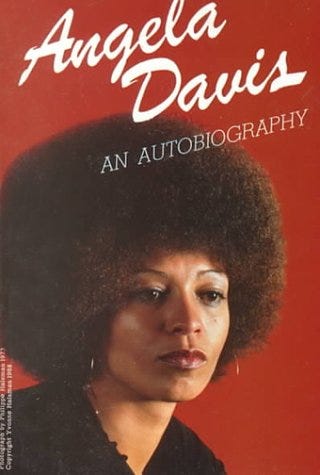

I think I cultivated a hopeful feminism because my first feminist love was Angela Davis. Angela Davis has always had an optimistic view of where we can go and an unwavering faith in the people. She credits her optimism with the fact that her mother would often tell her and her siblings to “never forget the world is not organized in the way it should be and that things will change, and that we will be a part of that change.” I did my first big chop right before I left for college and whenever I would style it in an afro people would call me Angela Davis. I only sort of kind of knew who she was. I knew who she was but only in the superficial way that most Black folks know her. She was an afro rocking, black leather jacket wearing, Black Panther revolutionary that terrified white people. The constant comparisons to her made me want to know more about who she was beyond the afro so I eventually I went to a local Black owned bookstore and bought her autobiography. I remember staring at that cover, completely captivated by her image. I know that Davis has spoken about the complexity of being reduced to a single hairstyle, but for me, her image called me in and served as a guidepost towards revolutionary thinking. In her image, I saw the familiar and that she was of and for Black women. That she was ours and we were hers and that what I would find in the pages of that book was a politics that would get me, and people like me, free.

I think I was subconsciously looking for manifestations of freedom when I found that book. I spent long durations of my formative years being systems-impacted which means that I was affected in a negative way by the incarceration of a close relative. Some of my earliest memories were me as a toddler piling into our 2-door car to drive to Quantico, VA to visit my father in the military prison there. My middle childhood memories include family trips to Rikers Island and long bus trips “Up North” to visit my cousin where we would eat mushy hot wings and microwaved cheeseburgers from the vending machine in the visiting room. As an adolescent, I played out my bratty little sister role by picking fights with my brother and running outside where he couldn’t chase me because his ankle monitor would go off. Confinement was an everyday part of my life and the people I knew would cycle between the block, the prison, and the block again.

I think I was yearning for the work of Angela Davis—particularly her work on incarceration. I found hope in the way she articulated that prisons disappear people not problems. In clear, concise language she put forth a framework that explained that the state uses prisons to manage the human consequences of racism and capitalism. Her work helped me understand that these prisons, which felt ubiquitous and unmovable to me, had a history and what I was experiencing was by design. Her analysis of the prison was thorough and I understood that the prison-state was deeply entrenched in almost every facet of my life. There was something in this notion that was ironically was ironically freeing. It’s like when people talk about the sense of relief they feel when they finally receive a diagnosis for a chronic condition. There is a sense of validation and liberation that comes with the naming of the thing that has caused them pain. The naming of the prison-industrial complex made the prison less random and mysterious for me. And with this new knowledge, I was Nancy Drew uncovering the prison state everywhere. I saw it in the schools, the playgrounds, the layout of our neighborhoods, and even our relationships. And I felt hope that if we could name it, we could change it.

I also found immense hopefulness in the way Angela Davis made Black women’s everyday ways of surviving and resisting the prison state visible. Her work made space for thinking about the intersections of state violence and intimate partner violence and in 2001, Critical Resistance the prison abolitionist organization she helped found teamed up INCITE Women of Color Against Violence to pen a transformative statement on the link between gender violence and the prison industrial complex. From their standpoint of living at the intersections of patriarchy and the prison-state, these organizers called out both the prison abolition movement and the domestic violence movement and demanded the need for need systems of accountability that do not ask us to ignore the violence that women face at the hands of men in our communities but that also does not invite the police into our communities where they cause more violent harm, sometimes to the very people they were caused to protect.

Davis’ work also helped me see the invisible gender-dynamics of the prison and it helped me articulate what I saw on all those weekend visits. I always thought it was odd that for all the “ride for my dawgs” lyrics in the music I was listening to, the charter buses Up North and visiting rooms were filled with women and children. While there are systemic reasons for this gender imbalance, the reality is that the supporting of people behind bars is largely women’s work. Regardless of the gender of the person on the inside, it is women on the outside who are organizing carpools, writing letters, buying JPay stamps and paying exorbitant collect call bills, sending magazines, and putting money on books. Women are the ones finding ways to parent the children they can’t tuck in at night and endure the violence of entering the prison in an effort to love. Angela Davis showed me to look to the women for how we get free because they are the ones who know how to penetrate the walls of the prison and show us the ways the walls are permeable.

Finally, I found immense hope in her belief in a world without prisons. Knowing the complexity of the injustices we face can be overwhelming. With so many things to fight for and against, it can be difficult to even know where to begin. Angela Davis made it clear to me that abolition is a worthwhile pursuit, even if we have no idea what that kind of freedom will look like. When I say I want a world without prisons, I am saying that I want a world where prisons are not the first solution to all our social ills. I hope more feminists take up this banner. Big systems can fail. They are falling now, but the powerful are catching the pieces and picking up the pieces to rebuild these oppressive structures. The walls of the prison are being replaced with ankle bracelets and virtual visitations. If we are not careful, they will sell us confinement in place of the progress we have been fighting for. But if feminists are at the forefront, with hope and possibility, we can be there to pick up the rubble and create something new and better.

When feminists take up the banner of abolition, we get to imagine what accountability processes look it and demand one that is all of us or none of us. Abolishing the prison would require funding schools, providing food, creating affordable and safe housing, more jobs, better social safety nets, health services an investment in people and communities. It is in the most micro levels. It is rethinking how we discipline our children, how we deal with conflict with our friends, how we structure our intimate relationships. It will also require that we get to the root causes of the harms we do to each other. And it is in resisting the notions of people as easily disposable “trash.” We don’t let people disappear. Instead, we hold on to humanity and accountability even when it is hard. We abolish the prison so that we can create communities where everyone can thrive. Angela Davis shows us that it is a worthy pursuit and that we are better for trying to get there, even if we have no idea where we are going.

So, I have a hopeful feminism because my introduction to feminism was through someone who had made hope a practice. She has been consistently optimistic about where we can go and the strength of the people. I am so grateful that my afro led me to Angela Davis and a grounded optimism that sees possibility and hope. I believe that we are at the precipice of building something new. At least, I hope so.

I really enjoyed this!